How to prevent cruciate ligament damage in dogs?

08 Aug, 2017

Cranial cruciate ligament (CCL) ruptures or partial tears are now thought to be the end stage of degradation of the ligament rather than a result of a sudden trauma, as historically thought. As such, there is increased importance in maintaining ligament health through preventative physical medicine like massage and exercise, nutrition and weight control.

What dogs are prone to cruciate ligament injuries?

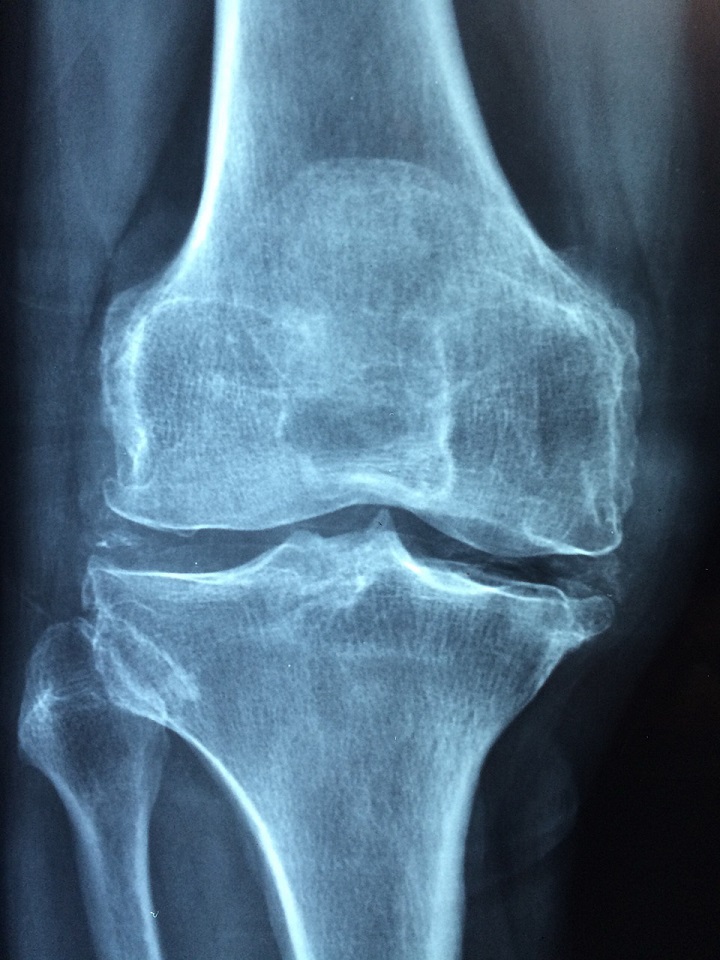

Cranial cruciate ligament rupture (CrCLR) is one of the most prevalent causes of hind limb lameness in dogs and often affects dogs with no history of lameness or trauma. Partial or complete rupture of the ligament results in joint instability and the onset of osteoarthritis.

In 10 – 17% of CrCLR cases, dogs present with bi-lateral CrCLR (both stifles affected simultaneously). Even when only one ligament is damaged the risk of a rupture in the contralateral CCL within 12 – 17 months is 40 – 60% which heightens the importance of prevention.

What is the cause of cranial cruciate ligament damage in dogs?

Causal factors of CrCLR include:

- Breed disposition

- Age related degeneration

- Obesity

- Joint conformation

- Joint immune responses

As CrCLR affects dogs with no history of lameness when they are performing normal activities, it is now thought that CrCLR is the end of a degenerative process that causes a rupture of the mid-section of the ligament.

Historically, degenerative processes such as osteoarthritis in the stifle were considered to be secondary to the CrCLR. However, causative relationships between immune responses in the joint and CrCLR are now more widely accepted. Inflammation of the synovial membrane has been positively correlated with CrCLR and is thought to be a key factor in the degeneration of the cranial cruciate ligament. It substantially reduces the strength of the CrCL by degrading the quality and condition of the ligament matrix. This can result in a rupture.

Across several canine studies, 50 – 67% of dogs with CrCLR, stifle synovitis (inflammation) was identified. Synovitis of the stifle is characterised by the infiltration of the synovial membrane with inflammatory cells. The inflammation increases vascularity (density and size of blood vessels) and affects the reproduction of synovial tissue over time. It results in damage to the ligament, menisci and cartilage in the stifle.

A study of dogs with CrCLR in one stifle found that these dogs also had arthritis and evidence of CrCL degradation in the stable joint. Dogs with more severe synovitis in the unstable joint also had more severe changes in the stable joint. It was concluded that while both joints are inflamed, the stable joint was at an earlier stage of the degenerative process than the joint with the CrCLR. In the stable joints of these dogs, there was evidence of CrCL damage ranging from tears in individual fibres to large disruptions of up to 30% of the ligament structure.

How to reduce the risk of CrCL injury?

Preventative medicine like massage, exercise and nutrition can assist in maintaining the integrity and strength of the dog’s stifle. Key preventative measures may include:

Avoid movements that place undue stress on the stifle joint and may result in a trauma.

Sudden cutting and pivoting motions should be avoided. However, for dogs that perform these types of movements as part of their “jobs” such as herding or agility dogs, then good preparation and conditioning is important to maintain joint health.

Conditioning may include regularly performing exercises that strengthen the musculature, tendons and ligaments of the hindquarters particularly those that support the stifle. Exercises may include swimming, underwater treadmill walking or trotting or hill walking. For more information on exercises to build dog’s muscles please see: http://www.fullstride.com.au/blog/exercise-to-build-your-dog-muscles

Prior to rigorous exercise performing a good warm up will help reduce the risk of injury from a sudden trauma.

Avoid weight gain

Excess weight strains the dog’s joints and may cause deviations in the dog’s movement. See https://www.fullstride.com.au/blog/obesity-and-osteoarthritis-in-dogs for more information.

Nutrition should also be considered as a way of addressing inflammation in the dog’s body.

Address lameness, pain and inflammation in the stifle

Massage along with stretching is effective in addressing lameness by reducing muscle tension and relieving painful spasms and trigger points. When pain is the result of joint inflammation, massage stimulates the circulatory system to create a flushing effect that removes the mediators of inflammation around the joint. Massage has also been shown in some studies to have a modulatory effect on inflammation by manipulating macrophage concentrations.

Has your dog suffered a CrCLR? What steps are you taking to prevent a rupture on the other leg? Leave me a comment here or on the Full Stride Facebook page to share your experience.

Full Stride provides canine massage treatments to keep dogs happy, mobile and active. For more information please contact me. . (I respond to all enquiries within 24 hours, so if you don’t receive a response, please check your Bulk Mail folder or give me a call.)

Until next time, enjoy your dogs.

Sources:

Barrett, J. G., Hao, Z., Graf, B. K., Kaplan, L. D., Heiner, J. P., & Muir, P. 2005. Inflammatory changes in ruptured canine cranial and human anterior cruciate ligaments. American journal of veterinary research, 66(12), 2073-2080.

Bleedorn, J. A., Greuel, E. N., Manley, P. A., Schaefer, S. L., Markel, M. D., Holzman, G., & Muir, P. 2011. Synovitis in dogs with stable stifle joints and incipient cranial cruciate ligament rupture: a cross‐sectional study. Veterinary surgery, 40(5), 531-543.

Doom, M., De Bruin, T., De Rooster, H., van Bree, H., & Cox, E. 2008. Immunopathological mechanisms in dogs with rupture of the cranial cruciate ligament. Veterinary immunology and immunopathology, 125(1), 143-161.

Goats, G,C. 1994 “Massage-the scientific basis of an ancient art: Part 2. Physiological and therapeutic effects”, British Journal of Sports Medicine 28 (3) p153 – 156

Klocke, N. W., Snyder, P. W., Widmer, W. R., Zhong, W., McCabe, G. P., & Breur, G. J. 2005. Detection of synovial macrophages in the joint capsule of dogs with naturally occurring rupture of the cranial cruciate ligament. American journal of veterinary research, 66(3), 493-499.

Waters-Banker, Christine 2013 “Immunomodulatory effects of massage in skeletal muscle”, Theses and Dissertations – Rehabilitation Sciences, Paper 18